Early History of the Hippodrome Theater: 1914-1920

Pearce and Scheck’s historic Hippodrome Theatre was built in 1914,

on the eve of World War I.

The Hippodrome was designed by Thomas W. Lamb, the pre-eminent theater architect of his day. The Hippodrome was an important transitional project in the career of Thomas Lamb. Born in Scotland, and without formal architectural training, Lamb began practicing architecture in 1892 after an apprenticeship as a building inspector, which involved him in the practical considerations of theater construction. By the time he was working on the Hippodrome, Lamb had established a reputation as one of the nation’s leading theater architects. He designed more than 300 vaudeville theaters and movie palaces worldwide with his longtime collaborator Marcus Loew. At least 12 of Lamb’s theaters are listed on the national Register of Historic places. His heralded work abroad includes theaters inEngland, Australia, North Africa, India and Egypt.

The Hippodrome was designed by Thomas W. Lamb, the pre-eminent theater architect of his day. The Hippodrome was an important transitional project in the career of Thomas Lamb. Born in Scotland, and without formal architectural training, Lamb began practicing architecture in 1892 after an apprenticeship as a building inspector, which involved him in the practical considerations of theater construction. By the time he was working on the Hippodrome, Lamb had established a reputation as one of the nation’s leading theater architects. He designed more than 300 vaudeville theaters and movie palaces worldwide with his longtime collaborator Marcus Loew. At least 12 of Lamb’s theaters are listed on the national Register of Historic places. His heralded work abroad includes theaters inEngland, Australia, North Africa, India and Egypt.

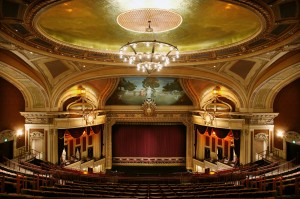

Although Lamb’s work reflected a simpler style, the Hippodrome represents one of the last opulent designs from his early period and is an outstanding example of early 20th century theater design. A richly textured, sculptural façade of ornamental brickwork framed three arches, and a magnificent terra cotta frieze and cornice crowned the building. The lavishly decorated and dynamic interior, originally a palette of creams, tans and brown accented in silver and gold, focused on the elaborate proscenium arch and stage. Above the proscenium arch, Vincent Maragliotti’s richly colored allegorical painting survived despite extensive damage from water, and age. Painted in 1914, the mural is the hallmark of the theater. It is 26 feet high and 45 feet at the base, and forms an unusual truncated bell curve. The composition is an allegory featuring goddesses from Greek mythology which might appropriately be called The Triumph of the Performing Arts. The central figure of Athena (goddess of the arts) is flanked by Clio (muse of history) and Terpsichore (muse of lyric poetry and dance) on either side and Thalia (muse of comedy) and Melpomene (muse of tragedy) on the extreme right and left, respectively. Page Conservation, Inc. of Washington, DC, recommended the mural be repaired so the mural received conservation treatment from Conrad Schmidt Studios, Inc. of New Berlin, Wisconsin as part of the renovation before the theater reopened in 2004.

Billed as “the largest theater south of Philadelphia” when it opened, the Hippodrome quickly became the most fashionable place in town. Loew’s operated the theater featuring live vaudeville; it was an integral part of the west side, Baltimore’s vibrant entertainment district. The Iron Master was the first film to be shown at the theater in November 1914. A two reel movie, it was accompanied by seven vaudeville acts. A typical vaudeville program from 1915 included an orchestra performance followed by trapeze performers, “Thompson’s Elephants,” “Barlow’s Dogs and Ponies,” “Webb’s Seal’s,” and “Arizona Days” featuringAmerica’s greatest cowgirl rider, Adel Von Ohl. The list of noted figures who performed at the Hippodrome runs from the stars of vaudeville such as the flamboyant Sophie Tucker, to stage actress Ethel Barrymore, comedian Red Skelton, the multi-talented entertainer Danny Kaye, and bandleaders Cab Calloway, Glenn Miller, Guy Lombardo, and the “King of Swing” Benny Goodman. Frank Sinatra made his solo debut performance with the Harry James Orchestra on June 30, 1939. Flight to Marsand The Highwayman in December 1951 marked the end of the showing of a vaudeville combined with a movie and began double movie bills. In November 1967, Gone with the Wind played at the Hippodrome but, due to a one alarm fire, was cut short and patrons had to be evacuated. Up in Smoke in 1978 was the last film to be shown at the Hippodrome.

The Hippodrome also played an important part in Baltimore entertainment history in 1917 when it became the first theater in the City to show motion pictures. Designed to host vaudeville shows as well as the new moving picture technology, the Hippodrome was one of the earliest dual purpose theaters in the country. By 1920, the Hippodrome and two nearby theaters were drawing 30,000 patrons per week to three daily performances.

The Decline: 1960-1990

By 1960, the Hippodrome was beginning to show its age, with a shrinking audience and gradual disintegration of the surrounding neighborhood.

After almost thirty years, Rappaport was beginning to withdraw from actively managing the Hippodrome. The theater was leased for a twenty year period to the Trans Lux Corporation, a major chain of east coast motion picture theaters.

Trans Lux spent a reported $150,000 renovating the theater. The Rappaport marquee was replaced with a much smaller stainless steel version. The large vertical Hippodrome sign that had been there from the opening of the theater in 1914 was also discarded. By the late 1970’s the frieze and cornice at the top of the building were weak and were removed rather than reinforced. These changes greatly altered the appearance of the façade of the theater. Drastic changes were also made inside the theater. To fight the competition from television, Hollywood began experimenting with a variety of wide screen techniques like Vistavision and Cinerama. This technology required wide, curved screens stretching across the front of the theater. To accommodate this equipment, the proscenium boxes and their canopies were removed from either side of the screen. Sometime during the 70’s, the crystal chandelier that was hanging above the orchestra disappeared and was never replaced. The elaborate stenciling and gold leaf on the ceiling was covered with grey paint. Many other theaters were renovated during this decade as well. The popular method for decorating the walls was to cover them with fabric. Pink polyester fabric was hung from floor to ceiling, even covering the mural above the stage.

The new theater decoration did not look anything like the theater Baltimoreans had come to love. Even though the theater was big, with the new design it felt claustrophobic. One critic even described the effect as “sitting in a coffin”.

In the spring of 1968, after the assassination of Martin Luther King, Baltimore experienced the inner city riots that affected many cities across the country. By this time, only three downtown film theaters remained open and their continued operation was uncertain. The audiences that came to the Hippodrome had changed considerably. In order to adapt, the theater began to show blaxploitation and kung fu films. The showing of violent films was a survival technique that characterized the theater as a “grind house”. Nonetheless, the Hippodrome remained open for two more decades.

By 1990, all audiences had dried up and an August edition of The Sun headlined: “Hippodrome Closed Forever.” Fortunately, this was not the case.

Continental Realty, the company that owned the theater at this time, was unsuccessful in its efforts to rent or sell the building. No one was even interested in tearing it down. The company did not consider it economically viable for them to maintain or renovate the theater or redevelop it for other purposes. Because of this, they made the decision to donate the Hippodrome to its neighbor: the University of Maryland at Baltimore.

The Eutaw/ Howard Street corridor had been the central shopping and theater district in Baltimore since the early part of the twentieth century. Unfortunately, by the close of the century all of this activity had migrated to the suburbs. The West Side was a deserted, core on the west side of a city where the focus was in other areas. It was even referred to as the “wild west”. But that would change in the new century.

Recent History of the Hippodrome Theatre: 2004-Present

After it was abandoned for ten years, the Hippodrome underwent a $70 million dollar renovation which included the absorption of two banks and other property on the block bordered by Fayette, Eutaw, Paca and Baltimore Streets and reopened February 10, 2004 with The Producers the new Mel Brooks Musical.

The new center, called the France-Merrick Performing Arts Center has become an anchor on the west side of Baltimore.

The new center, called the France-Merrick Performing Arts Center has become an anchor on the west side of Baltimore.

The new Hippodrome solved a problem Baltimore had been facing: The economics of Broadway were such that Baltimore was not going to get shows at the Morris A. Mechanic Theater; it had too few seats to make it worth it for producers. With over 2000 seats and a state of the art new theater, the Hippodrome provided a place for producers to bring the biggest and most popular shows (e.g. Disney’s The Lion King, Wicked, Motown The Musical, The Color Purple etc.). The building has contributed to both the city and state economies with millions of dollars spent on the Westside of Baltimore City. Crowds continue to enjoy seeing major shows right here.